- Sam Bankman-Fried bilked FTX customers out of more than $8 billion, according to prosecutors.

- FTX bankruptcy lawyers say they could get all their money back.

- The judge sentencing Bankman-Fried on Thursday has to grapple with that gulf — as well as his autism diagnosis.

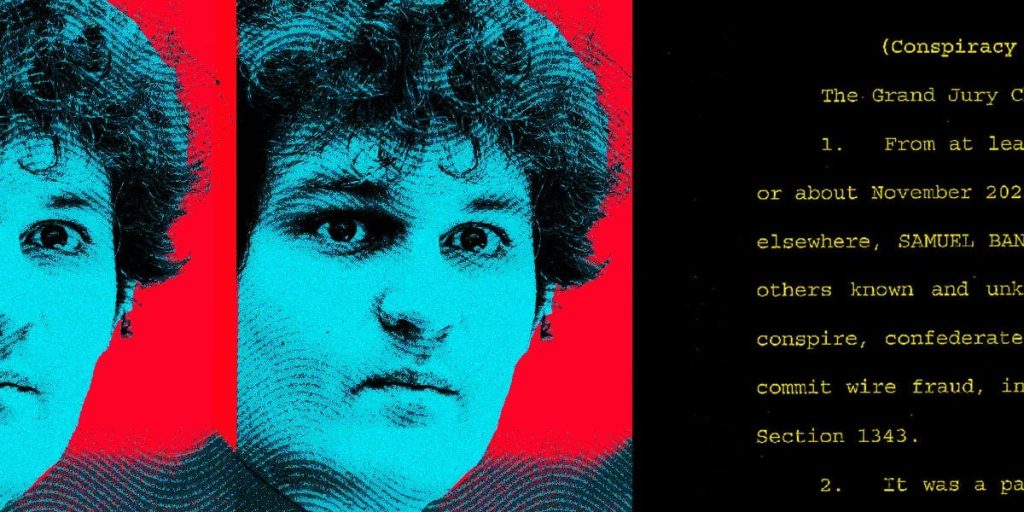

According to federal prosecutors, Sam Bankman-Fried orchestrated one of the biggest criminal frauds in the history of the world. Customers of FTX, his cryptocurrency exchange, lost more than $8 billion, they say.

According to his lawyers, FTX’s customers may get all their money back.

Their dispute leaves a four-decade gap between how long prosecutors want the ex-crypto boss to serve in prison and the much lower 6 ½-year sentence his lawyers are fighting for.

The judge who’s set to sentence Bankman-Fried on Thursday is being asked to address this vast gulf. He’s expected to decide how much money the convicted fraudster should be held accountable for. He’s also being asked to weigh the entire circumstances of Bankman-Fried’s life, including whether he should be treated differently than a run-of-the-mill fraudster because of an autism diagnosis.

Bankman-Fried’s criminal case is inextricable from the complicated bankruptcy of FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange he was convicted of using as a vehicle for his fraud.

He was arrested in December 2022, just about a month after FTX collapsed and declared insolvency under a new CEO, the seasoned executive John J. Ray III, who was tasked with shepherding the ruins of FTX through the bankruptcy court. Since the arrest, the criminal cases against Bankman-Fried and his coconspirators — other executives who have pleaded guilty and largely cooperated with prosecutors — worked on a parallel legal track to FTX’s bankruptcy proceedings.

As Bankman-Fried sat in his parents’ home, under house arrest, he purported to make efforts to help out with the bankruptcy process. Offering to help identify FTX’s assets, he repeatedly emailed Ray, who spurned him.

Shortly after he took over the company, Ray told the court there was “a complete absence of trustworthy financial information.” Bankman-Fried complained about being shut out, insisting to journalists and friends that he could have helped locate FTX’s scattered assets.

US District Judge Lewis Kaplan, who presides over Bankman-Fried’s criminal case in lower Manhattan, precluded all talk of the bankruptcy proceedings from the monthlong trial. Bankman-Fried’s criminal culpability rested on intent to defraud, not how much money customers actually lost, he ruled.

All jurors heard about was how Bankman-Fried used billions of dollars in customer money, not any steps he might have taken to recover it later.

The complicated math of FTX’s losses

In November, jurors found Bankman-Fried guilty on all counts, including fraud, conspiracy, and two different kinds of money laundering.

According to prosecutors, Bankman-Fried was responsible for more than $11 billion in fraud overall between FTX customers and investors in FTX and Alameda Research. He spent it all on flashy advertising, real estate, tech investments, political contributions, and charity donations.

In the months after the trial ended, things started looking better for FTX’s customers. The artificial-intelligence boom was in full swing, and a $500 million investment that Bankman-Fried made using their money was looking prescient. Within the last month, some cryptocurrency prices — after diving with FTX’s collapse — reached new highs. In a January 31 bankruptcy hearing, an FTX debtor lawyer told the bankruptcy court that FTX customers and creditors “will eventually be paid in full.”

While the jury wasn’t given the chance to consider it, Kaplan himself is soon getting to decide whether the fact that Bankman-Fried’s victims may get their money back — and how he did or didn’t contribute to that — will factor into his sentence.

Judges ultimately have wide latitude in what they’re allowed to consider while imposing a sentence. Sarah Krissoff, a white-collar defense attorney at Cozen O’Connor, says that whether they should consider the intended loss or genuine loss is a hot legal dispute that will probably end up in front of the US Supreme Court.

If Bankman-Fried went to trial an hour’s drive away, in a New Jersey district court, the judge would have worked under the jurisdiction of the United States Third Circuit Court of Appeals and considered actual loss. But because he was tried in New York, controlled by the Second Circuit, the intended loss is what matters, Krissoff says.

“If you intend to steal $5 million, and you steal $2, it’s still driven by that $5 million number,” Krissoff, who was a former federal prosecutor in New York, told Business Insider.

In their sentencing submission, prosecutors say Bankman-Fried shouldn’t be rewarded for how he spent other people’s money. Bankman-Fried’s attorneys have argued that the lack of customer losses should cut in his favor, but prosecutors say that doesn’t account for the efforts of FTX’s bankruptcy lawyers, who had to liquidate real estate, cancel contracts, and sue to claw funds back from K5 Global, a celebrity-connected investment firm that Bankman-Fried invested money into.

Ray, who’s stewarding FTX through its bankruptcy process, wrote in his own scathing letter to the judge that Bankman-Fried left the company as “a metaphorical dumpster fire.”

“The value we hope to return to creditors would not exist without the tens of thousands of hours that dedicated professionals have spent digging through the rubble of Mr. Bankman-Fried’s sprawling criminal enterprise to unearth every possible dollar, token or other asset that was spent on luxury homes, private jets, overpriced speculative ventures, and otherwise lost to the four winds,” he wrote.

Ray also said many of the things Bankman-Fried spent customer money on couldn’t be recovered.

“There are plenty of things we did not get back, like the bribes to Chinese officials or the hundreds of millions of dollars he spent to buy access to or time with celebrities or politicians or investments for which he grossly overpaid having done zero diligence,” he wrote. “The harm was vast. The remorse is nonexistent.”

The recovered calculations, too, distort how much money customers are actually getting back.

FTX’s depositors would be repaid based on the dollar value of their cryptocurrency holdings at the time that FTX declared bankruptcy.

So if someone purchased one bitcoin on FTX’s exchange at the price of $60,000, and then bitcoin dropped to $20,000 in November of 2022 — which can be at least partly attributed to the chaos of FTX at the time — their credit is worth $20,000. It doesn’t matter if the price of bitcoin has risen back to over $60,000 since then. The creditor would get $20,000, not $60,000.

Rachel Maimin, a former New York federal prosecutor, said the value of FTX’s assets after bankruptcy ultimately had nothing to do with Bankman-Fried.

“It has nothing to do with the circumstances of the offense itself,” Maimin, now a white-collar defense attorney at Lowenstein Sandler LLP, told BI. “It’s totally separate from that. This is something that happened almost by luck after the offense was complete.”

Bankman-Fried’s lawyers and family want the judge to consider autism symptoms

Bankman-Fried’s lawyers and family members have made other entreaties to the judge. They have said he exhibits behavioral characteristics associated with neurodivergent people and have asked Kaplan to judge him accordingly.

“I genuinely fear for Sam’s life in the typical prison environment,” Barbara Fried, Bankman-Fried’s mother, wrote in a letter to the judge. “Sam’s outward presentation, his inability to read or respond appropriately to many social cues, and his touching but naive belief in the power of facts and reason to resolve disputes, put him in extreme danger.”

Neurodivergence can manifest in several ways, including autism, dyslexia, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In their sentencing submission, his defense attorneys attached a letter from Hassan Minhas, a psychiatrist who said he met with Bankman-Fried for four hours in July 2023 and diagnosed him with autism spectrum disorder.

Minhas wrote that Bankman-Fried “does not have any intellectual deficits and in-fact he presented as intellectually gifted” but “demonstrated deficits in being able to read social-cues, and appropriately respond to them.” He added that while Bankman-Fried had “made attempts to compensate” for those deficits, he’d probably exhibit those symptoms for the rest of his life.

“The deficits persist and may present in various settings as him being socially awkward or inappropriate, not understanding social nuance, or responding in ways that may be perceived as off-putting to others,” Minhas wrote.

About 2.2% of adults in the US have autism, according to the Centers for Disease Control in 2017. Minhas said the “social deficits” associated with autism would make it more challenging to interact with prison staff and other incarcerated people. He recommended that Bankman-Fried get access to psychotherapy and that personnel be trained to “inform their interactions with him.”

Bankman-Fried’s lawyers also included a letter from the psychiatrist George Lerner, who described himself as the “in-house coach at FTX” and wrote that the former FTX executive was “on the autism spectrum.”

“I believe that his psychiatric conditions led others to misinterpret his behavior and motivations,” Lerner said.

Prosecutors, in their 116-page sentencing memorandum, didn’t address the topic of Bankman-Fried’s neurodiversity at all. They say Bankman-Fried’s life and characteristics — he grew up in a stable home with caring parents, went to an elite college, and worked at an elite Wall Street trading firm — show that he knew exactly what he was doing.

“The defendant chose to abandon honest work to pursue profit and influence through crime, and he used the proceeds of those crimes to enjoy his own lifestyle of affluence,” they wrote. “The fact that he chose to engage in a massive fraud is an aggravating factor, not a mitigating one.”

Bankman-Fried’s diagnosis may come up again in an appeal. During the trial, lawyers and jail staffers tussled over access to his prescribed medication that he said he needed to focus for his defense.

It’s in the judge’s hands to decide how much neurodivergence should matter.

“You’d have to show that his divergence had some effect, I would think, on his judgment, his ability to understand right and wrong,” Maimin, the Lowenstein Sandler attorney, told BI.

Maimin said that, in any case, the Federal Bureau of Prisons dealt with various neurological issues all the time.

“The BOP handles people with an enormous range of medical problems, including psychological problems, neurological problems, and probably has a not insignificant population of neurodiverse people, and is able to handle that,” she said.

At this point, Kaplan has formed his own view of Bankman-Fried.

It doesn’t appear to be positive.

Before the trial, he ordered Bankman-Fried to be jailed after finding that he repeatedly violated his house-arrest conditions and engaged in witness tampering, including for leaking personal journal entries by Caroline Ellison, his ex-girlfriend and the former CEO of Alemda Research, and by sending text messages to an FTX lawyer offering “a constructive relationship.”

When Bankman-Fried took the witness stand for his criminal trial, often giving circuitous answers, the judge didn’t find his testimony very convincing.

“Part of the problem,” Kaplan said, “is that the witness has what I’ll simply call an interesting way of responding to questions.”

Correction: March 28, 2024 — An earlier version of this story misstated whether Sam Bankman-Fried’s lawyers disclosed an autism diagnosis. In their February sentencing submission, they included a letter from a psychiatrist diagnosing him with autism spectrum disorder.

Read the full article here