Few western capitalists admit to taking inspiration from China’s Communist party, but when Michel Doukeris moved to Shanghai in 2009 to run the Chinese arm of Anheuser-Busch InBev he was quickly taken with Beijing’s five-year plans.

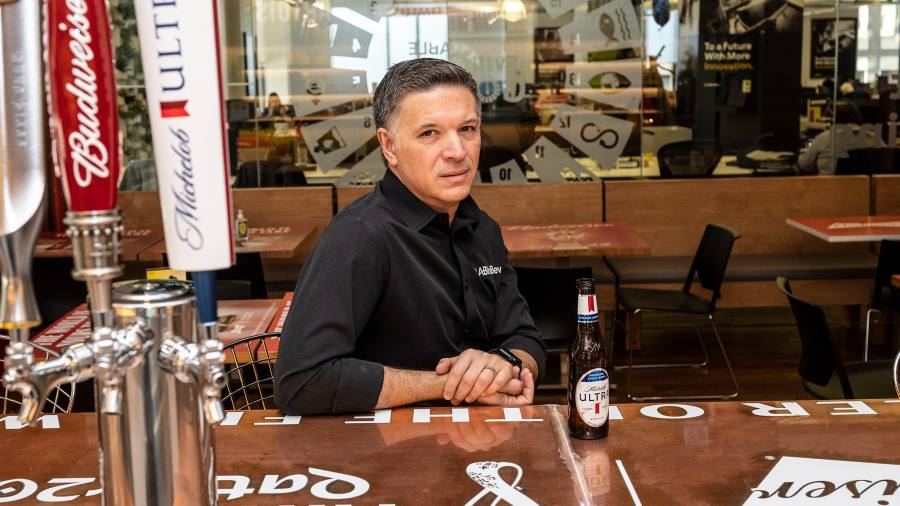

His success in turning round unprofitable operations in Asia and then reviving brands such as Budweiser in the US helped land Doukeris the top job when Carlos Brito, whose dealmaking built a Brazilian beer company into the world’s largest brewer, retired as chief executive in 2021.

The lesson in long-term planning Doukeris learnt in China has shaped a management ethos with which he is repositioning a group built by debt-fuelled acquisitions for a changed economy and a changing consumer.

“The big click that came to me when seeing this five-year plan . . . in China was this very structured assumption that you want to build things on a more long-term basis,” he recalls in an interview in New York, too early in the day to be conducted over a Corona or Stella Artois.

Rather than looking five years ahead, though, he is pushing colleagues to plan for what suppliers, retailers and consumers may want in a decade. Such thinking can make near-term challenges seem a little smaller, he argues, and if AB InBev can identify trends early and invest accordingly, its competitors will struggle to catch up.

“It’s almost like you avoid a battle for something by positioning yourself ahead of everybody else for that thing. You’re fighting the fight but without having direct confrontation,” he says. Doukeris had another reason for focusing AB InBev on a longer horizon. He had been with the company for 25 years before becoming chief executive, but as the new boss taking over from a powerhouse who led it for 15 years, he was anxious to send a message that he would be around for a while.

“I’m here for the long term. I will not rush through decisions . . . We will do things that will last,” he says.

AB InBev did not exist before 2008, and it only sealed its transformative merger with SABMiller in 2016, but it trades on a history that goes back to 1240, when the canons of an abbey in Leffe, Belgium, took up brewing. Not quite two years into the CEO’s role, Doukeris is already talking about his own part in that story.

“We have great history. What we need to do now is build the capabilities that we need for the next 100 years. And when people look backwards to this generation, these people at this point, they will understand what was the legacy that we left behind,” he says.

One of his first tasks was to come up with a clearer definition of the company’s purpose. A “soul-search” consultation settled on two messages: that each of AB InBev’s brands began with somebody “dreaming big”; and that its goal is to create “a future with more cheers”.

What he likes about these slogans is again their long-term nature. “A future with more cheers” is “like an infinite game, where there is always a next step”, he says: “I want the company to be able to be stretching this boundary over and over again.”

Asked how he differs from his predecessor, Doukeris lauds Brito’s record while noting that his own career has involved more time in its operations, rather than at headquarters. He is “obsessed” with building things to last, he says. Another distinguishing feature may say more about the balance sheets the two men inherited than about their leadership styles.

“We built the company by acquiring things, not by creating things,” Doukeris observes. He has done plenty of M&A himself, “but my passion was always more on the building, rather than buying”.

His prioritisation of organic growth over dealmaking is a message investors want to hear from a company whose net debt reached 5.5 times its earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation in 2016. Continuing work Brito had started, Doukeris has brought that down to 3.5 times, but with $80bn of debt remaining at the end of last year he has more to do. AB InBev’s share price has rallied in the past six months but is still below its pre-pandemic level.

Doukeris is helped by a culture that watches costs almost obsessively. Under Brito, AB InBev became one of the business world’s most ardent proponents of zero-based budgeting, with managers having to justify each expense anew each year, from printer paper to office rent.

“Every dollar that is spent counts,” Doukeris says, noting that he personally bought the ballpoint pen he is fiddling with. The constant attention to expenses may have saved the company from having to make sudden headcount cuts as inflation began to bite, he suggests, but he contends that outsiders overstate zero-based budgeting’s impact on its culture.

When he became CEO, Doukeris realised he would have to rely more on other people than he had in his previous jobs, and that the information they brought him would be “curated”, and not the full picture.

He has tried to avoid the “theatre” of overprepared presentations from his direct reports. Instead, he asks them for monthly “performance memos” — two or three-page notes where they tell him what’s working, what’s not, and what they want to discuss with him.

He supplements these with annual “listening tours”, where he meets the company’s top 200 leaders in small groups. “Individually, none of these conversations of five to 10 people make sense because the topics are very random,” he says, but recurring themes emerge when his team distils their notes of the meetings.

These have helped shape four key assumptions about what AB InBev’s market will look like over the next decade.

First, that the recent industry trend of “premiumisation” — encouraging drinkers to trade up to pricier brands — has further to go. Second, that the beer, spirits and wine categories will blur further, while creating more demand for alcohol-free alternatives and lower-alcohol options such as spritzers.

Third, Doukeris predicts, its dealings with stores, bars and consumers will become increasingly digital. It has created an online marketplace to help small convenience stores restock with its products and those of other brands, which 6mn outlets now use. “If the community’s healthy, if the customer is growing, then we have a better business,” he observes.

Finally, Doukeris believes demand for beer will keep growing, and that the strongest growth will be in less saturated markets where AB InBev thinks it is well positioned, from Latin America to Africa and from India to China.

Returning to the seven years he spent in Asia, Doukeris says China taught him a style of lateral thinking at odds with conventional western business logic. Presented with 1,000 different ways to go from A to B, western executives will hunt for the single most efficient route, he says, but “if you prepare everything and you launch with only one outcome, which is success, maybe you overcommit for that thing”.

The alternative is a style of rapid experimentation which he is now promoting. “You take multiple routes, and you decide which one’s more effective, and you kill several very early on,” he says. The approach has cut the time it takes to launch a product from as much as four years to as little as 100 days.

“This idea that things are only good when they work out, actually, this is not true,” he says: not doing a deal may be the best outcome from an M&A project, for example.

Doukeris may be pushing a long-term message but he also wants his company to experiment now and learn quickly from its mistakes. “Failing fast and failing cheap is actually a great achievement,” he says.

Read the full article here