About the authors: Mary Hayes is research director for People and Performance at ADP Research Institute. She has a doctorate in educational leadership from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Nela Richardson is chief economist at ADP and head of the ADP Research Institute. Richardson earned her doctorate in economics from the University of Maryland, College Park.

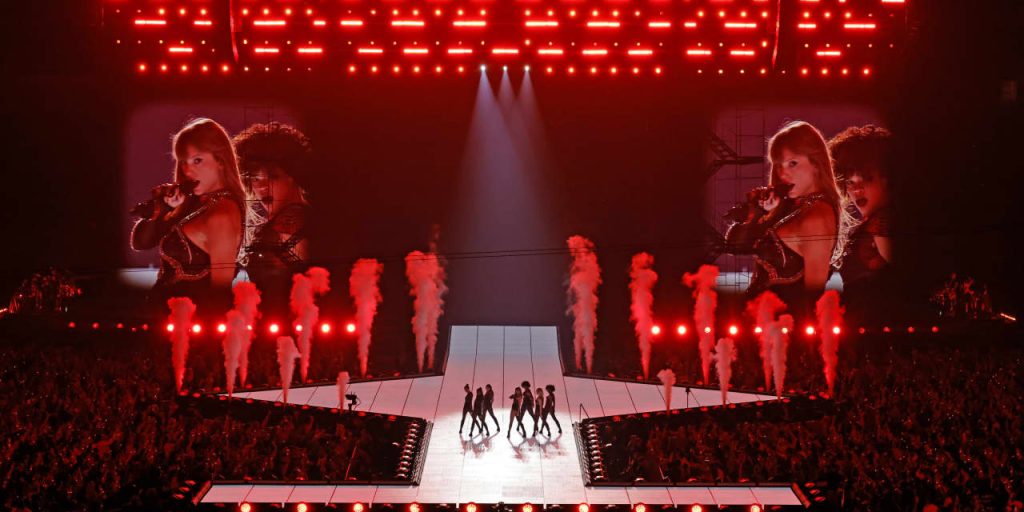

Women reached a significant milestone this summer. While Barbie was in theaters and Beyoncé and Taylor Swift were breaking concert tour records, labor force participation for women aged 25 to 54 reached its highest level in more than 25 years.

This milestone was nearly four years in the making. Job losses for women topped those of men during the pandemic for the first time in U.S. economic history. Health concerns left millions of women pulled between work and new family responsibilities. As workers, women also were concentrated in industries hit hardest by social-distancing restrictions, such as retail and leisure and hospitality.

Female prime-age participation fell hard and fast, dropping from 77% in February 2020 to 73.5% in April 2020, a near-record low, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The turnaround was swift, too. Labor force participation reached 77.8% in June 2023.

But that important recovery might now have stalled. Since this summer, prime participation rates among women have softened, falling to 77.4% in September. After a hot summer for working women, data from the ADP Research Institute suggests that a new wave of departures might be under way.

We dug into the payroll data of more than 25 million U.S. workers to calculate the number of hours women are working and see whether there’s been a downward shift in their labor activity. The results are troubling.

Our data shows that women have struggled to make up economic ground as they’ve returned to the labor market over the last four years. There also are emerging signs that peak participation is over. The share of women in the workforce shrank by two percentage points, from 48% to 46%, between March and May 2020.

As of September, women make up 47% of hourly workers, still a percentage point short of prepandemic levels.

Moreover, the percentage of part-time workers both male and female has increased since before the pandemic. In February 2020, the share of people working fewer than 40 hours a week stood at 37%. As of September 2023, the part-time worker share is 41%.

Women have led this increase in part-time workers. While they make up less than half of all workers, they make up more than half—56%—of part-time workers.

The gender gap in hours worked also has widened. The typical woman worked 35 hours a week in September, two hours less than she did in February 2020. The typical workweek for men has remained unchanged at 40 hours over the past four years.

Women are earning less than men, among prime-age workers, because of that gap in hours. Women in that group also earn less per hour than comparable men. For women 35 to 55, their earnings fall to 73% of what men earn.

Not only are women working less and earning less, they also are heavily concentrated in high-turnover industries, such as education, health services, and leisure and hospitality. New hires—employees with less than three months on the job—made up more than 10% of workers in these industries, double their 5% share in the overall labor market.

With the participation rate of women starting to ebb only a few short months after reaching a record high, the question at hand is how do we get them to stay in the labor market?

In any given month, about 60% of all workers are engaged in “leaving behavior,” according to a sentiment survey fielded by the ADP Research Institute. The prevalence of this behavior, which includes browsing job listings, talking to recruiters, actively looking, and scheduling interviews, suggests that the job market is in a constant state of flux.

Surprisingly, we found no gender differences between the groups of workers who are looking for a new job and those who aren’t.

Yet there are big gender differences when it comes to worker motivation on the job and commitment to their employer. Our sentiment data shows that 32% of men are highly committed and motivated, compared to 27% of women.

For workers between 40 and 54, 29% of men are highly motivated and committed, compared to 23% of women. These differences even out after age 55, when family responsibilities tend to be more balanced between the genders.

This analysis holds the key to helping women stay in the labor market.

Organizations have the ability to slow the revolving door of workers. They can build trust and ensure that pay is equitable, for starters. Building trust between workers and their supervisors or management can nurture an employee’s desire to stay with the organization.

Across our survey sample of more than 55,000 respondents, women are only slightly less trusting than men of their leaders. But when trust is strong, women are 3.8 times less likely to leave their organizations.

Guest commentaries like this one are written by authors outside the Barron’s and MarketWatch newsroom. They reflect the perspective and opinions of the authors. Submit commentary proposals and other feedback to ideas@barrons.com.

Read the full article here