America has a glut of empty offices.

Now, some offices face losing WeWork, which has more than 600 locations in major cities.

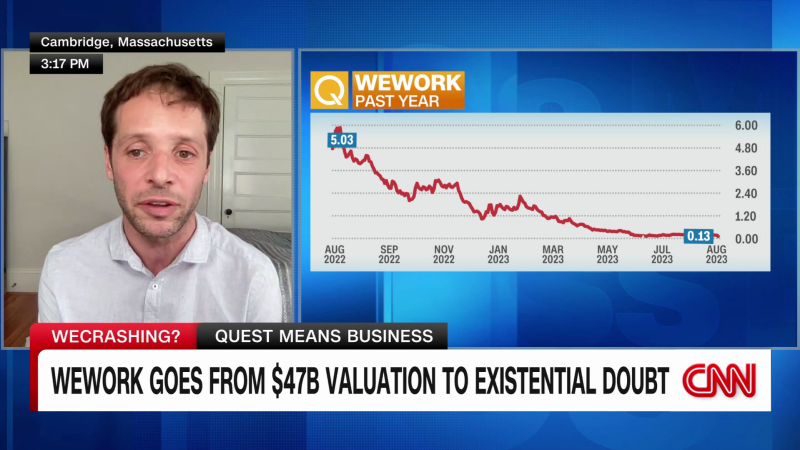

WeWork filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy Monday, throwing the future of the real estate company up in the air. WeWork said it would terminate some of its US leases.

WeWork’s bankruptcy will increase financial stress on commercial landlords that have rented large chunks of their office buildings to the co-working company.

Office landlords for years rushed to rent out space to WeWork, viewing flexible office spaces as the future of office life. But these bets have soured, and some property owners have taken on debt to stay afloat. About $270 billion in commercial real estate loans held by banks will come due in 2023, according to Trepp, a commercial real estate data provider.

The loss of WeWork will increase vacancies, might lower rent for tenants, meaning less cash for some landlords already struggling to make debt payments in a high interest rate environment, commercial real estate experts say. In the worst case scenario, it may prompt landlord defaults on loans or mortgages, which could more broadly affect the banking system and hit city tax revenues even further.

“Office properties – already facing financing hardships and [lower] values – now face a potential new wave of unexpected vacancies,” Moody’s economist Ermengarde Jabir said in a report Tuesday.

The bankruptcy could have a ripple effect on smaller and mid-sized banks holding landlords’ debt, causing banks to tighten loans to home and business owners, and stoking investor anxiety about the health of the financial system. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank earlier this year sparked fears about banks’ exposure to hard-hit commercial real estate. Goldman Sachs estimates that 55% of US office loans sit on bank balance sheets.

It could also hurt municipal governments that rely on commercial property taxes to provide services, potentially leading to budget cuts. In New York City, for example, office properties make up 21% of tax revenue.

“WeWork’s bankruptcy is a major shock to the office market, especially because the market was in deep trouble,” said Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, a real estate professor at Columbia Business School. “This is another huge problem for the office market to contend with.”

No single tenant can make or break the office market, he said. But “as much as any one tenant can matter, WeWork would be it.”

Offices in New York City, San Francisco and Boston will be hit hardest by WeWork’s bankruptcy, experts say.

Around 42% of WeWork’s occupancies are in those three cities, according to CoStar, a commercial real estate data firm. WeWork already has plans to close 1.9 million square feet in these three markets, about 35% of its footprint.

In New York City, where WeWork was once the largest corporate office tenant, WeWork’s active leases are heavily concentrated in older “Class B” buildings. These offices were already seen as less appealing for possible tenants than newer “Class A” assets.

WeWork’s Class B buildings are, on average, 96 years old, while Class A buildings are 48 years old. Around 65% of WeWork’s leases are in Class B properties, compared to 30% in Class A properties, according to CompStak, a real estate firm.

“WeWork’s larger exposure to Class B buildings, in particular, is less than ideal for the NYC office market because many market participants are concerned about office obsolescence and falling demand in that same class of buildings,” Alie Baumann, CompStak’s director of real estate intelligence, said in an email. In New York City’s Class B buildings, for example, the average purchase size for a new deal has dropped 36% from 2019 levels.

WeWork’s rents in those buildings also were higher than the rest of leases, so landlords can’t easily recoup lost rent from other tenants.

WeWork’s bankruptcy comes as more than one-fifth of offices across the United States remain vacant, according to commercial real estate giant JLL.

Commercial real estate was hit hard by the pandemic, with fewer people returning to offices and spending money in downtown corridors. Companies have reduced their office footprints and renegotiated rents.

The rapid increase in interest rates over the past year has been painful for the sector, since purchases of commercial buildings are typically financed with large loans.

“It’s the latest setback after a year of rising interest rates and high levels of maturing debt,” Baumann said.

Landlords will look to replace WeWork with new tenants, likely at lower rents, but some may not be able to fill WeWork vacancies.

“Since many of their leases are in Class B buildings, where most generally agree demand is weaker, landlords may face an uphill battle in filling that space,” she said.

Other owners will try to convert their buildings to alternative uses, such as health care, higher education or apartments. But conversions are difficult because some buildings don’t lend themselves well to, say, new apartments or meet regulatory requirement.

“There are not that many great options,” said Van Nieuwerburgh from Columbia. “I expect Class B and C buildings to end up being stranded assets until they go through bankruptcy and are bought for pennies on the dollar.”

Read the full article here