It has been three years since workers started telecommuting in vast numbers, but state tax laws still haven’t adapted to the new remote-work paradigm and individual taxpayers are paying the price with exasperating state tax-filing procedures.

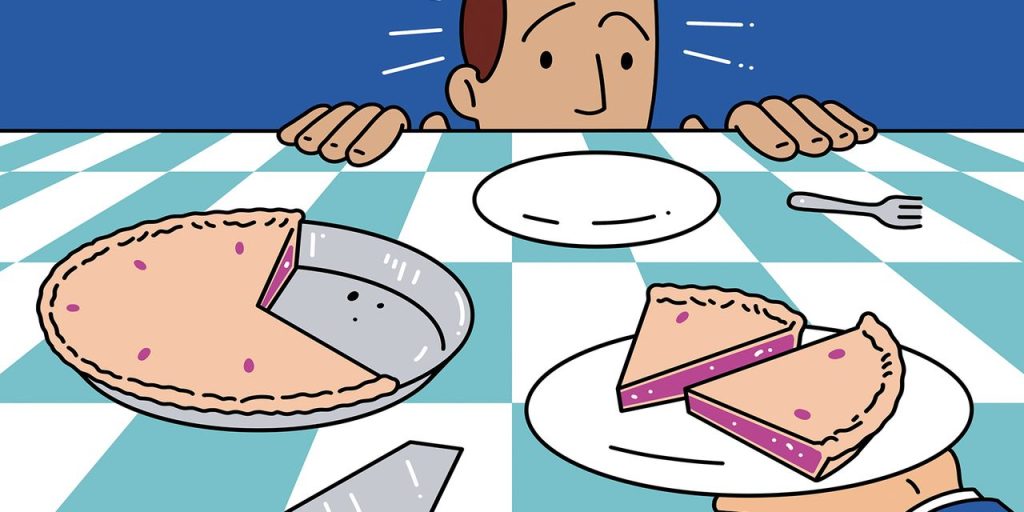

Many taxpayers who work remotely in a different state than their employer’s must prepare multiple state 2022 tax returns and account for precisely how many days they worked in the company office versus locales in other states—whether at home, at a vacation house, at the in-laws, or elsewhere.

In many other situations, taxpayers have to pay all state taxes on wages to their employer’s state—often at a higher rate than their home state—even if they haven’t stepped foot in their employer’s state for the year.

Another layer of complexity occurs for people who work remotely for more than half a year in a state that isn’t their official residence. This can create a double tax on their investment income.

With substantial revenue at stake, some states have been flexing audit muscles to collect what they are due.

“I’ve personally seen more New York audits in past three years than I’ve seen in my career,” says Craig Richards, chief administrative officer for Fiduciary Trust International.

The problem for remote workers is that state tax rules are all over the map—quite literally—which means your personal filing requirements depend on the tax rules of your home state, the state where your employer is located and any other state you worked from temporarily.

Generally, taxpayers are subject to taxes on earned income in the state in which they work. If you aren’t a resident where you work, most states require you to file a nonresident tax return and pay taxes for the days of work within its borders, but state rules vary. Maine, for instance, allows nonresident taxpayers to work within its borders for up to 12 days without filing a nonresident tax return. In North Carolina, you have to file for any number of days worked.

The state where you reside has the right to tax all of your income, but taxpayers can usually claim a credit for any taxes paid to other states.

Many states have tried to make things simpler for remote workers by establishing reciprocity agreements with other states to allow taxpayers to only pay taxes to their resident state, even if they work in another state.

Seventeen states and Washington, D.C., have reciprocity agreements with certain other states. For example, Ohio has a reciprocity agreement with Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Maryland, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Arizona has one with California and nonadjacent states including Indiana, Oregon and Virginia.

But there are a handful of states that don’t play so nice.

New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Delaware and Nebraska have so-called convenience of employer rules, under which they tax workers whose employers are based within their borders, even if the workers have a part- or full-time arrangement to work remotely in another state.

“If your employer is in New York and you live in New Jersey or Connecticut, you can’t claim a work-from-home day as a non-New York day from New York’s perspective,” says David Devin, a Stamford, Conn., CPA.

Revenue loss for some commuter states has been substantial. In 2020, New Jersey remote workers paid more than $1 billion to New York, according to the New Jersey Department of the Treasury.

During the pandemic, New Jersey, Connecticut and 11 other states filed amicus briefs in a U.S. Supreme Court case brought by New Hampshire against Massachusetts after Massachusetts temporarily adopted a convenience rule to be able to tax New Hampshire residents employed by a Bay State company, even if they worked remotely.

The states sought to restrict tax authorities from collecting taxes earned beyond their borders. In late 2021, the court declined hearing the case.

Massachusetts ended its temporary convenience rule, but New York and the other states maintain theirs and, in response, Connecticut passed its own convenience rule last year just in relation to New York or other states that have a convenience rule. New Jersey has proposed a similar measure.

The only way to avoid paying taxes in states with convenience of employer rules is if you can prove you are working from home by necessity, not convenience.

But it can get messy, says John Biello, deputy commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Revenue Services. “New York might say a taxpayer is working out of convenience at home, Connecticut might say, ‘No, it’s out of necessity that they are working from home,’ and the taxpayer could have tax liability in both jurisdictions,” Biello says, but adds that his office doesn’t have data on the frequency of such conflicts.

The New York Department of Taxation and Finance didn’t reply to calls seeking comment for this article.

Even if you work out of an official satellite office, preparing for state taxes can be an enormous headache, Devin says.

Say you work in Connecticut, and occasionally spend time working in New York City. You would have to prorate your taxes between New York and Connecticut very carefully, because New York is notorious for digging into your records to make sure it’s getting its fare share, he says.

“If you travel for a day and use the New York airport, that has to be counted as a New York workday,” Devin says. “A client had a New York audit, and it was excruciating to prove where he was every day.”

Even if you pay all tax to a state like New York with a convenience of employer rule, if you worked in other states temporarily you can get dinged for not filing a nonresident tax return.

If you work for a few days in North Carolina, you could face non-filing penalties and interest to North Carolina for not filing a tax return, says Scott Roberti, Ernst & Young’s U.S. State Policy Services leader.

The potential for double taxation comes into play if you spend more than 182 days—half a year—working in a state other than your official resident state, says Elizabeth Pascal, a partner at Hodgson Russ. If you do, that state can consider you a statutory resident and can, along with your official resident state, tax your investment income.

“You may get a credit for taxes paid on wages, but when it comes to interest, dividend and capital gains that’s not always the case—it depends on the states,” Pascal says.

Richards says he has a New York client who decided to work remotely in Vermont. Despite warnings that overstaying the 182 days would mean both New York and Vermont would tax his investment income, he chose to stay in the bucolic state and pay state income taxes twice. “Not every decision is dollar driven,” Richards says. “Sometimes it’s based on lifestyle.”

While these have been perennial issues in state taxation, the number of taxpayers impacted has exploded since remote working arrangements normalized during the pandemic.

Currently about 30% of work is conducted remotely, down from about 60% during peak pandemic months but elevated relative to the 4.7% prepandemic norm, according to WFH Research, which runs a monthly survey on work arrangements and attitudes.

“Unfortunately states still have not come to the table with reforms,” says Jared Walczak, vice president of state projects of Tax Foundation. “A few states have explored ways to make it easier or more practical for remote workers, but we’ve made no progress.”

Write to [email protected]

Read the full article here