There is a reasonable chance that you’ve at least heard of Australian real estate developer Tim Gurner. He is the millionaire employer who declared that “there’s been a systematic change where employees feel the employer is extremely lucky to have them as opposed to the other way around,” and that unemployment needed to rise by 40% or 50%, there needed to be pain in the economy and that “we need to remind people that they work for the employer, not the other way around.”

Gurner eventually apologized, according to Sky News. Gurner’s apology said, “My comments were deeply insensitive to employees, tradies [trade workers in construction], and families across Australia who are affected by these cost-of-living pressures and job losses.”

What else was he going to say at that point?

It isn’t often you hear an executive publicly say something so brazen and entitled. But this attitude is far from new. In the 1990s, I was sitting with a group of executives who had been in a board meeting. One of them that I knew mentioned something he had read by Earl Nightingale, that workers should understand they were lucky to have a job.

I’ve never read anything by Nightingale but understand that he grew up during the Great Depression, with a father that left the family, meaning that Nightingale, his brother, and his mother had to live in federal housing. He knew what it was like for people who couldn’t find jobs, no matter how hard they tried.

Having a job for millions was and is important and a stroke of luck. Perhaps that is part of what Nightingale meant. Or maybe not.

But the person quoting Nightingale, someone who had grown up in relative economic luxury, was repeating this story and in the way that Gurner intended. Employees should regard the employer as a benefactor who was owed fealty and diligent effort to do anything the company required.

Such a one-sided view gets to the heart of why the strikes in Hollywood have gone on so long (even assuming that the Writers Guild members will vote in favor of the new negotiated contract). A look at employee compensation and corporate profits helps explain how things have moved out of an historical balance.

Anyone who says that worker entitle are off in an historical context have the picture upside down. It is the employers whose expectations have skyrocketed, who have taken more while delivering less.

The Screen Actors Guild has pushed back hard against studio demands that they should be able to digitally capture images of many performers and then use them with ratification intelligence animation as puppets. The studios want to own the essence of performance for one-time payment. To own the future work someone could provide without additional compensation. To drain them of future potential earnings.

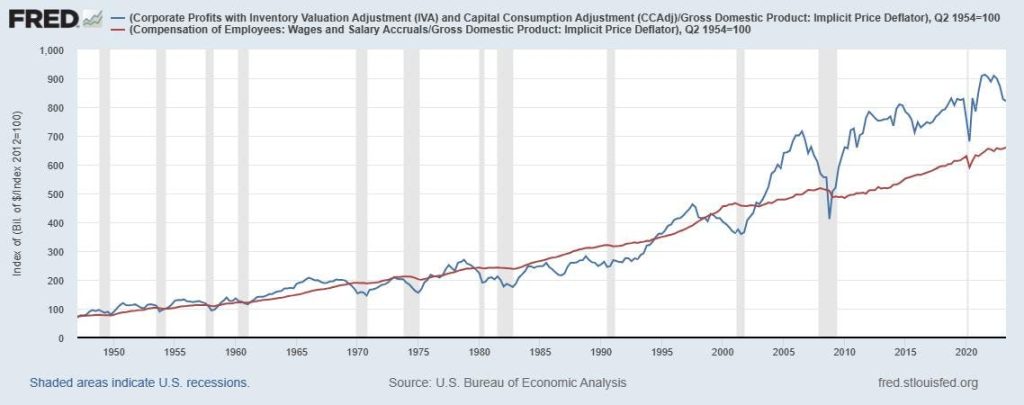

Historically, employees didn’t push for outrageous compensation. It grew over time as did inflation. Companies also kept roughly along a line though with a lot more volatility, following the ups and downs of business cycles, making more when times were good, making less during recessions. However, over time, corporate profits took over, soaking up a greater percentage of revenue and reducing the possible compensation of workers because more was pocketed by shareholders and executives.

The old equilibrium is gone, which is why there is so much strike activity these days. Employees are demanding a right-sizing of the relationship and a return of the traditional balance. People who need jobs are fortunate that there are companies to provide them; however, companies really are fortunate that people will work for them. Pushing too far on either side upsets everything and creates situations like that of trucking company Yellow Corp. The workers were willing to lose their jobs because they felt there was nothing left.

Read the full article here